formerly: Rubber Factory

full archive here

full archive here

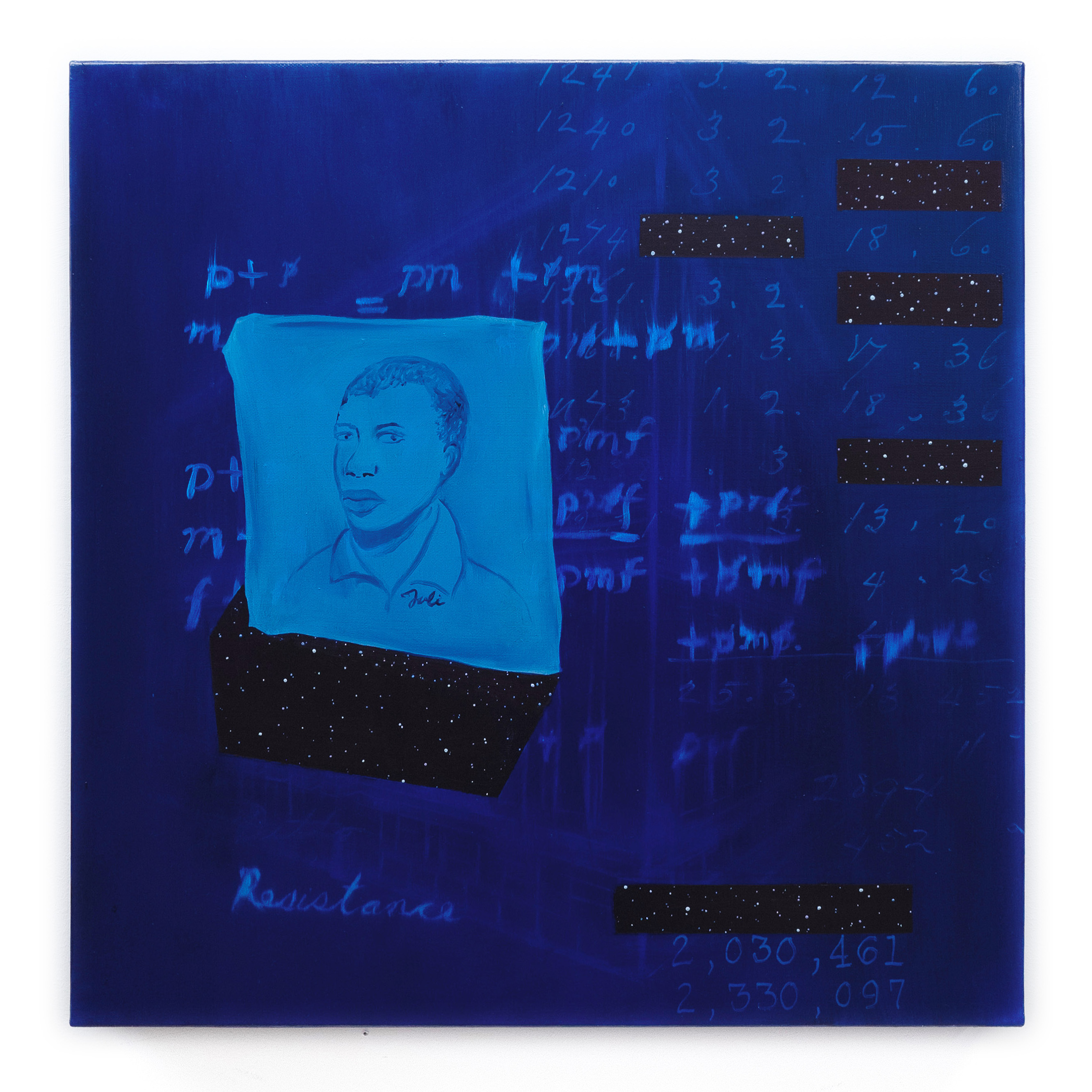

island gallery is pleased to present night grass, a new solo exhibition by Alex Callender. In these works, narrative acts like a set of spectral encounters. Botanical renderings, pages from merchant ledger books, and industrial agriculture, draw water lines from one space to the other, sometimes interrupted by the presence of figures. An image of a slave’s portrait alongside notations from a trade ledger recalls the form factor of a passport photograph and the machinations of an empire. Tender, ghostly renderings of other figures hint at a sort of historical slippage where these figures are real yet unaccounted for.

In “the waterline at the center of the myth”, a view of Boston’s colonial harbor opens up into a second Atlantic space, exposing the rising waters that intimately entwined New England to the slave societies of the Caribbean. In Callender’s paintings, blue represents the water, the cloth, the map, the tarpaulin tent, the lament, the unease, (un)freedom’s blueprint; the possibility for life. In the work, “Unsettling palimpsest, even haunts the grass”, a scene of families is depicted promenading around military line exercises at West Point, imagery featured in the Zuber Company's 1836 panoramic wallpaper, Views of North America. The figures are imposed as a ground or foundational myth, now covered by a mix of wild aster, turf, and bluestem grass. The historical memory inside Zuber’s illustrated views of pastoral New England and New York, produced during the Jacksonian era, tell a more complicated story where site/cite expand to reveal the plantation geography of the Caribbean as part of the ghostly doppelganger of the American North’s economic ascendance.

Callender imagines a nightscape of the West Point military scene in the painting, “At this time of night there is no one place or the other and I see you clearly”. Emerging through the wallpaper, a woman appears holding an image taken from a Cuban pineapple plantation, reminding us of America’s long 19th century desire to occupy Cuba as a plantation outpost. The stereoscopic image that she is looking through is in and of itself an imaginary landscape, altering our relationship to the land by rendering it a visual captive.

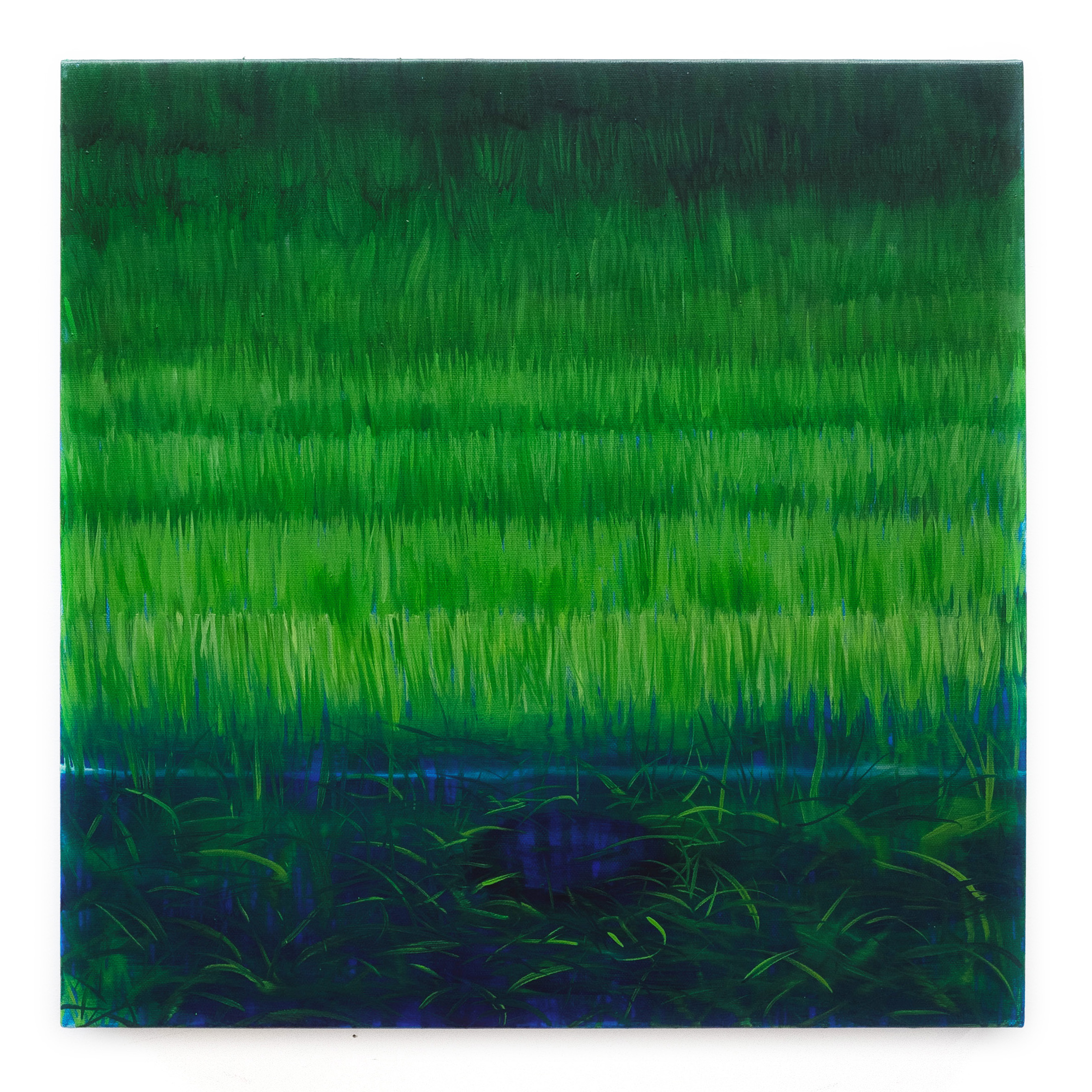

In the exhibition, grass performs a dual role of delineating the landscape into parcels to be possessed, as well as acting as an untamable element encroaching upon the pictorial plane. In “the settler state wandered, looking to make new borders but the rising water washed all the lines away and there was nowhere else to go”, cane, cordgrass, and virgata grasses tell a story of absence and presence, plantation, industry, monoculture, and the many migrations carried by float and force across the waters.

Alex Callender’s practice uses methods of drawing, painting, and installation to trace and remap historical materials as a means to explore with both criticality and care, how we might disentangle the interwoven relations of race, gender, and capitalism. Callender has had solo exhibitions and projects at the Center for the Arts Northeastern University, UMass Contemporary Museum of Art, NYU Gallatin Galleries, the Rubber Factory (NY), and Michigan State University’s LookOut Gallery. Alex has received artist grants from the Pollock-Krasner Foundation and the Massachusetts Cultural Council and has held artist residencies with MacDowell Colony, The Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Lower Manhattan Cultural Council, The Drawing Center’s Open Session program, Art in Embassies Program, The Vermont Studio Center, the Santa Fe Art Institute, Alice Yard in Trinidad, and DRAWinternational and The BAU Institute in France. Callender is currently an Associate Professor of Art at Smith College.

In “the waterline at the center of the myth”, a view of Boston’s colonial harbor opens up into a second Atlantic space, exposing the rising waters that intimately entwined New England to the slave societies of the Caribbean. In Callender’s paintings, blue represents the water, the cloth, the map, the tarpaulin tent, the lament, the unease, (un)freedom’s blueprint; the possibility for life. In the work, “Unsettling palimpsest, even haunts the grass”, a scene of families is depicted promenading around military line exercises at West Point, imagery featured in the Zuber Company's 1836 panoramic wallpaper, Views of North America. The figures are imposed as a ground or foundational myth, now covered by a mix of wild aster, turf, and bluestem grass. The historical memory inside Zuber’s illustrated views of pastoral New England and New York, produced during the Jacksonian era, tell a more complicated story where site/cite expand to reveal the plantation geography of the Caribbean as part of the ghostly doppelganger of the American North’s economic ascendance.

Callender imagines a nightscape of the West Point military scene in the painting, “At this time of night there is no one place or the other and I see you clearly”. Emerging through the wallpaper, a woman appears holding an image taken from a Cuban pineapple plantation, reminding us of America’s long 19th century desire to occupy Cuba as a plantation outpost. The stereoscopic image that she is looking through is in and of itself an imaginary landscape, altering our relationship to the land by rendering it a visual captive.

In the exhibition, grass performs a dual role of delineating the landscape into parcels to be possessed, as well as acting as an untamable element encroaching upon the pictorial plane. In “the settler state wandered, looking to make new borders but the rising water washed all the lines away and there was nowhere else to go”, cane, cordgrass, and virgata grasses tell a story of absence and presence, plantation, industry, monoculture, and the many migrations carried by float and force across the waters.

Alex Callender’s practice uses methods of drawing, painting, and installation to trace and remap historical materials as a means to explore with both criticality and care, how we might disentangle the interwoven relations of race, gender, and capitalism. Callender has had solo exhibitions and projects at the Center for the Arts Northeastern University, UMass Contemporary Museum of Art, NYU Gallatin Galleries, the Rubber Factory (NY), and Michigan State University’s LookOut Gallery. Alex has received artist grants from the Pollock-Krasner Foundation and the Massachusetts Cultural Council and has held artist residencies with MacDowell Colony, The Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Lower Manhattan Cultural Council, The Drawing Center’s Open Session program, Art in Embassies Program, The Vermont Studio Center, the Santa Fe Art Institute, Alice Yard in Trinidad, and DRAWinternational and The BAU Institute in France. Callender is currently an Associate Professor of Art at Smith College.